A dozen or so people in flip-flops and aqua socks line the small bay’s shore in Rapa Nui (Easter Island). Kids with zinc oxide residue on their faces squish shoreline silt between bare toes. Some adults chat. Others gaze out at the canoeing on the bay.

Uri Araki Oyarce, an early 40s Rapanui* man and experienced ocean paddler with the boundless energy of a late 20-something rookie, stands waist-deep in the water. He’s demonstrating to a vaka full of first-timers how to hold their hoe [for terminology, see the note which follows the article below].

Everyone does their best to replicate Uri’s instructions as he offers gentle corrections, supplies positive reinforcement, and cracks the occasional self-deprecating one-liner to help them loosen up. Muffled hoe vaka commands travel across the bay as another vaka circles inside it. Soon, the shorebound group will have their turn too. It’s a typical Saturday in Haŋa Piko (hang-gah-pea-koh, “hidden bay”).

Overlooking the scene from the shore, up on a knoll of dehydrated grass one of Rapa Nui’s moai statues stands sentinel. Pre-pandemic, thousands of tourists flew over five hours from Santiago, Chile every year to see these monolithic moai. But the Saturday folks in aqua socks are island residents; they’re here to paddle. Five years ago, they might not have had this chance. It wasn’t until 2017 that Uri founded the island’s first and only inclusive hoe vaka club.

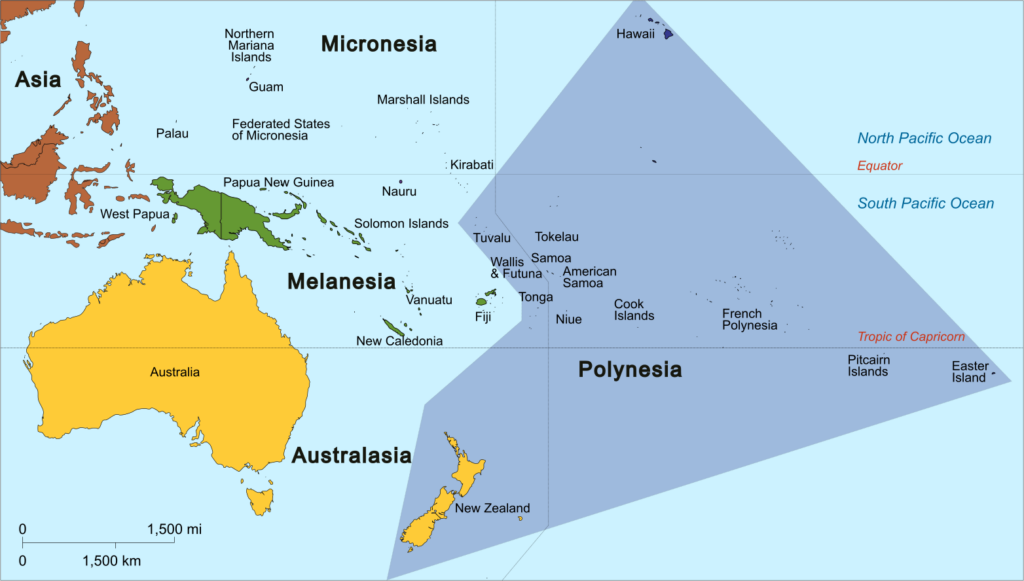

Hoe vaka is as much a Rapanui cultural legacy as moai. Before aeroplanes and modern ships, Polynesian sailors traversed large ocean expanses in vakas. In fact, the navigation routes of trans-Pacific ancient voyagers first ‘drew’ the lines of what’s now called the Polynesian Triangle.

Designed for long-distance ocean travel, vakas connect Polynesians geographically and culturally. This draws Uri. It’s a direct link to his past, and “how [his] ancestors arrived to this remote [one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world] and beautiful island.” Despite this pan-Polynesian cultural legacy, there was a centuries-long pause between distance voyages and on many islands, local hoe vaka too. Until the 1970s that is: some were practising hoe vaka on Polynesian islands before the ‘70s, but 1974 was a milestone.

In that year, the double-hulled voyaging canoe Hōkūle’a, ‘Our Star of Gladness’, successfully travelled to Tahiti using ancient Polynesian wayfinding techniques and without the aid of modern navigation instruments. Putting to rest questions of whether this type of travel was possible, a renewed sense of Polynesian pride and revitalisation of traditional voyaging practices rippled across the Pacific Ocean.

Rapa Nui is still riding this wave. Now with approximately 20 teams, 10 annual competitions, and teams travelling overseas to compete, hoe vaka made a comeback on this 163 sq km speck of island. Its most recent innovation is Uri’s inclusive hoe vaka. For residents of Rapa Nui, Team Varua may be their only viable option to share in this. In addition to its open-armed policy, Team Varua provides essential equipment — paddles, canoes, life vests, and bailing buckets.

What inspired Uri to create Team Varua? For him, the “considerable and principal role of this team is to incentivise people to enjoy hoe vaka [and] give people the chance to practise this incredible sport.” He also sees how “sports bring people together and give them a chance to socialise,” that they might not have otherwise. If more people thought this way about sports — as a way to enjoy, interconnect, and pursue social, emotional, and physical well-being — we might have healthier outcomes on a larger scale globally.

Like many of its members, Team Varua continues to grow. When asked how the team got its name, Uri explains that “Varua [means] spirit in the Rapanui language,” and at the beginning of Team Varua, those few who did show up used to joke, “it’s just us and the spirits.” As of January 2023, the team is approaching 90 members.

Team Varua’s core values reflect core realities of Polynesian voyaging. Successful paddling of a multi-person vaka doesn’t lend itself to individualism. The better paddlers work together and synchronise movement, the more efficiently and safely the vaka advances. Yet many contemporary teams may seek new members for their individual competitive edge — based on strength, speed, bringing something new to the table, or a relationship to someone in the canoe.

Through Team Varua, Uri mentions, creating a team based on sharing the beauty of this sport in a community, has made it possible to “teach [and work with] a large quantity of people of varying ages,” and to “help out children who are vulnerable and adults with disabilities.” Hoe vaka, for everyone. The young, the old, the differently abled. For the love of it. And community.

With continued growth in participant numbers, the acquiring of equipment has struggled to keep pace with the onboarding of members. Dues from Team Varua club members help cover equipment costs but often fall short. Vakas aren’t cheap, and dues are kept low so as not to be prohibitive. Even used six-person vakas run £4000 minimum. That’s ten months of Chilean Rapa Nui’s average minimum wage (£400/month). Team Varua recently bought their third canoe, but they’re already in need of another. That’s the top challenge.

Skills get passed on through the club as team members who advance in knowledge help train newbies. This shared learning and collaboration adds joy, strength, ownership, and vitality to the experience. Once one has the techniques and safety understanding for the open ocean, they can advance to join six-person paddles during the week.

There are, of course, some wonderful competitive and outcomes-oriented teams on Rapa Nui too. For example, the November 2022 Hoko Mai challenge, in which 12 crew members (nine Rapanuis, two Chileans, and one Hawaiian), covered a 500 km voyage to raise awareness about the importance of women in the world, urge for the protection of the environment, and celebrate the union of the islands of Polynesia. But hoe inclusivo opens doors for island residents in a way that no other team has. While Team Varua may not be for everyone, it is for anyone.

*A note on language: Uri’s quotes were translated from Spanish to English by the author. In honouring the local customs and language of Rapa Nui, words and spelling of locations, items, and concepts associated with hoe vaka (Polynesian outrigger canoeing) have been retained —

Rapa Nui: the island

Rapanui: used as an adjective, ex. “Rapanui man”

Hoe (ho-ay): paddle

Vaka (vah-kah): canoe in Rapa Nui in the Marquesas; wa’a (va-ah) in Hawai’i; va’a in Tahiti

Ama (ah-mah): outrigger

Hoe vaka: Polynesian-style outrigger canoeing