Every year in Nepal, as summer peaks and days start to become too hot and dry, the monsoon comes as a beautiful respite for many. The dry earth gets replenished and the forests and rivers are full of life. But perhaps the ones who anticipate the grey skies of monsoons most are the farming communities of Nepal, for whom the monsoon signals the start of the main plantation season. The season also means the beginning of the planting of paddy — the most important grain in the country.

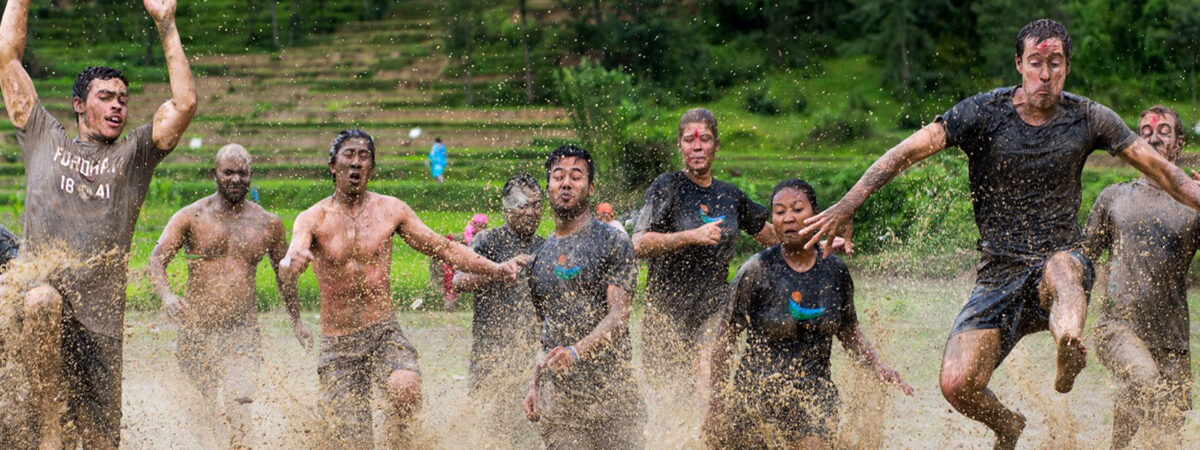

In fact, rice is so important here that come June every year, Nepalis observe National Paddy Day, locally known as ropain. The day falls on the 15th of the Nepali month of Ashar, typically towards the end of June. It is an important festival and is celebrated widely, as it symbolises the first planting of rice and is performed by farmers across the country. And in recent years, others, too, have become a part of the festival — with both locals and visitors planting rice saplings in the traditional style, enjoying mud fights with friends, dancing and singing together, and after plantation, eating a shared meal in the field.

I got to be a part of ropain celebrations for the first time back in 2021. At the time, Covid-19 lockdown restrictions had just been eased in the country and having been cooped up at home for months, getting a chance to be a part of the ropain festival and join in with something so communal felt all the more joyous and refreshing.

The ropain festival typically starts with a small puja, a ceremony where farmers pray for a good monsoon and a good harvest. Traditionally, the land is tilled by the men and the women plant the seeds; but roles today are not as restrictive. Once the soil is watered enough, it’s time to get your hands dirty! You squash the mud with water until it is mushy enough to scoop up and splatter around with your friends and farmers alike — making the experience special. After all the fun is had, you then plant the rice saplings in the mud. If you’re lucky, it might rain, which will make the celebration all the more fun.

After the planting is done, it’s time for a meal that’s shared by everyone. Traditionally, people eat beaten rice with curd — a combination that gives you energy and keeps you cool while working the fields. But these days, a larger spread is served; Newari delicacies such as choila (savoury barbequed meat), baatmas sadheko (spicy, fried soybeans), gundruk sadeko (dried, piquant spinach), aloo ko achar (potato pickles), and other side dishes. All of it is, of course, served with beaten rice, and washed down with a generous amount of chhyang (a fermented local brew, again made with rice!).

As you might have guessed, most meals in Nepali households are incomplete without rice. It is nearly always included in one form or another, whether beaten, puffed, boiled, or even as dessert. We eat rice at least once, if not twice, a day. It’s an important part of our lives and has huge significance in our culture. It also has deep religious significance — rice is a part of many important rituals, like pasni, a rice feeding ceremony that marks a child’s coming of age, the transition from drinking milk to eating solid food for the first time. It is also a part of one of Nepal’s most important Hindu festivals, Dashain, where rice grains are mixed with vermillion and placed on our foreheads in the name of blessings by the eldest members of a family.

Because of the historic cultural and religious significance of rice in Nepal, there is a huge demand for it. But farmers here are unable to meet this demand because most of them are subsistence and semi-subsistence in nature. Owing to this, there is a heavy dependence on rice imports. According to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), Nepal imported a staggering 947 times more rice than it exported in 2021. In addition to this giant trade deficit, prices are also on the rise and inflation is increasing, as reported in the Kathmandu Post — with Nepal Rastra Bank noting a 12.39 per cent jump in cereal grains and their products as compared to the same period of the last fiscal year.

There’s another problem with this deep dependence on rice: not any old rice will do. People prefer polished, long-grain, basmati rice, which has limited production in Nepal and again has to be imported, almost exclusively from India. This practice has resulted in local farmers planting basmati rice or other imported, hybrid strains, which has caused a decline in native varieties. Until some years back, farmers in different geographical regions of Nepal grew native breeds of rice, such as Aapjhutta, Jhapamansuli, Aanadi, Silange, Sano Jira, Bindeshwori, Mansuli, Marsi, Simtharo, among others. But now they have all switched to planting hybrid seeds — with encouragement from the government — because these seeds are more productive and cost-effective.

And while this is helping meet demand, it is endangering the very existence of many indigenous seeds, and with them, a lot of native knowledge and traditions. Considering the longterm consequences, is that a wise way to move forward? As we celebrate ropain, perhaps that could give us some good food for thought.