Nestled within the magnificent Karakoram Range, Hunza is an isolated heaven ringed by appealing snow-capped mountains. Shielded from the accessories of modernity and sheltered from the hustle and bustle of urban life, this beautiful locale portrays a peacefulness rarely found elsewhere.

Here dwells a hardworking community of warm-hearted individuals, reflecting both good physical health and sound mental well-being. Their lives are entwined with a love of nature and a healthy diet, notably influenced by an abundance of organic fruits such as apricots, apples, pears, and a plethora of other varieties thriving in a setting reminiscent of the Garden of Eden.

However, the joy of this heaven dims in the harsh winters of northern Pakistan. During this challenging season, the people of Hunza don’t have ready availability of fresh fruits. Instead, we rely on an old kind of strength that has been passed down through generations.

The secret of access to the delicious taste of organically preserved fruits during the winter lies in the hard work of each community member during the summer season. With great attention, locals preserve the fruit from their gardens, ensuring a lifeline of nourishment throughout the winters. And among the cherished fruits filling local orchards, the apricot reigns supreme.

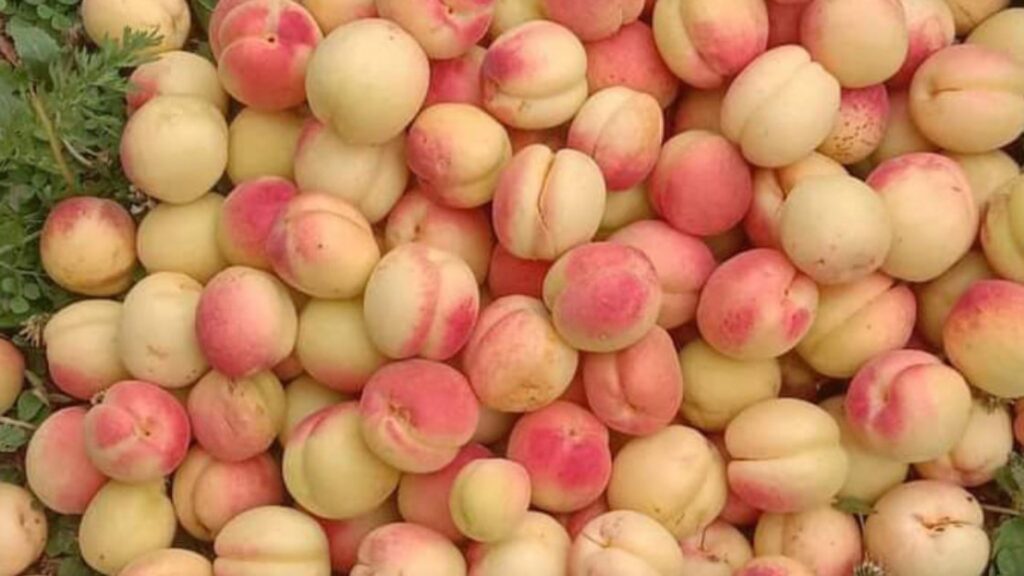

The delicately hued fruits provide a two-fold advantage through their seeds and flesh. From late June to mid-July, the orchards of Hunza are immense, with the sight of ripening yellow-orange produce stretching towards the horizon. The organic process of preservation starts when these juicy fruits are completely ripe and have achieved maximum sweetness.

Apricot drying begins with handpicking. We use ladders and specially made baskets, known as ‘girran’, for apricot picking. This method is essential as it is gentle on the fruit, preventing any bruising or damage and ensuring that only the ripest specimens are selected.

After the apricots are collected, the seeds are separated from the fruit. This can be done by splitting the apricots into two halves using our hands. As apricots are soft fruits, carefully opening and removing the pits is a simple yet time-consuming process.

After removing the seeds from the apricots, the remaining flesh is then spread out on locally crafted trays called ‘shaqqh’, making sure that the fruit is spread out in a single layer to ensure even drying. The fruit-filled shaqqh are placed in a sunny area for two days, where the warm sun and gentle breeze help to facilitate the drying process.

Next, the fruits are placed in a shadowy area under a tree for one week. This process allows the natural moisture in the fruit to continue evaporating gradually, leaving behind 90% dried apricots. Finally, the dry apricots are transferred to larger trays and are collected together in the same place for two weeks.

This step-by-step method allows us to dry them while preserving their original flavour (sweetness and a pinch of sourness) and maintaining their soft texture, avoiding making them too rigid and chewy.

However, at the time of the ripening of the apricot crop, the monsoon season begins, making it challenging for us to monitor the drying progress properly. We have to ensure the apricots do not come into contact with water or become wet, as this could impact the quality of the final product.

To combat dampness, after the initial drying process the dried apricots are usually placed in a ‘batarin a dapp’ basket. Along with the girann baskets used for gathering and the shaqqh trays where drying begins, the batarin a dapp are locally fashioned out of long stems taken from a unique tree, the Beek. With holes to assist in preventing the dry apricots from getting moist, these baskets play a vital role in encouraging the ventilation that helps dry apricots stay fresh.

But the real storage challenge begins after the apricots have been fully dried. Due to warm weather continuing until October, there’s a greater chance for the dry fruits to be infested by insect larvae. To protect the precious fruits of our labour, we use walnut leaves. When putting the dry apricots in the storage basket they are layered; after every layer, fresh walnut leaves are placed in between, helping to safeguard the sweet dry apricots.

It’s worth noting that the specific techniques and methods used by the Hunza people may vary within the community, for example among the Shinaki, Burosho, and Wakhi people, and there could be small variations in the process based on individual preferences and available resources.

But whatever the subtle differences, the result of all this hard work conveys the joy of fresh fruits in winter in various dishes like dried apricot juice (chamus) and dried apricot soup (bartarin-a-dawdo). Additionally, the seeds extracted from the apricots play a significant role in many traditional dishes of the Hunza culture like giyalin, burus-shapik, mulida, and many more. These dishes provide the apricot’s distinctive quality of sweetness with slight sour notes, while the apricot oil itself tastes similar to almond oil but with greater smoothness and a sweet aroma.

It is truly a fruit with endless benefits! From serving as a source of pride when furnished to guests, to offering protection from harsh weather while giving us the energy to stay warm; and from being a healthy, delicious snack, to providing a source of income for locals. It all springs from the humble apricot, reminding us of the fragrant joy of a summer garden during the harsh winters of the Karakoram Range.