As long as there are bridges, man continues to think, to create, to exist. The road does not end because there is a cliff, a river, or a sea ahead. The road is our persistence, and the bridge is the continuation of what we’re not ready to give up.

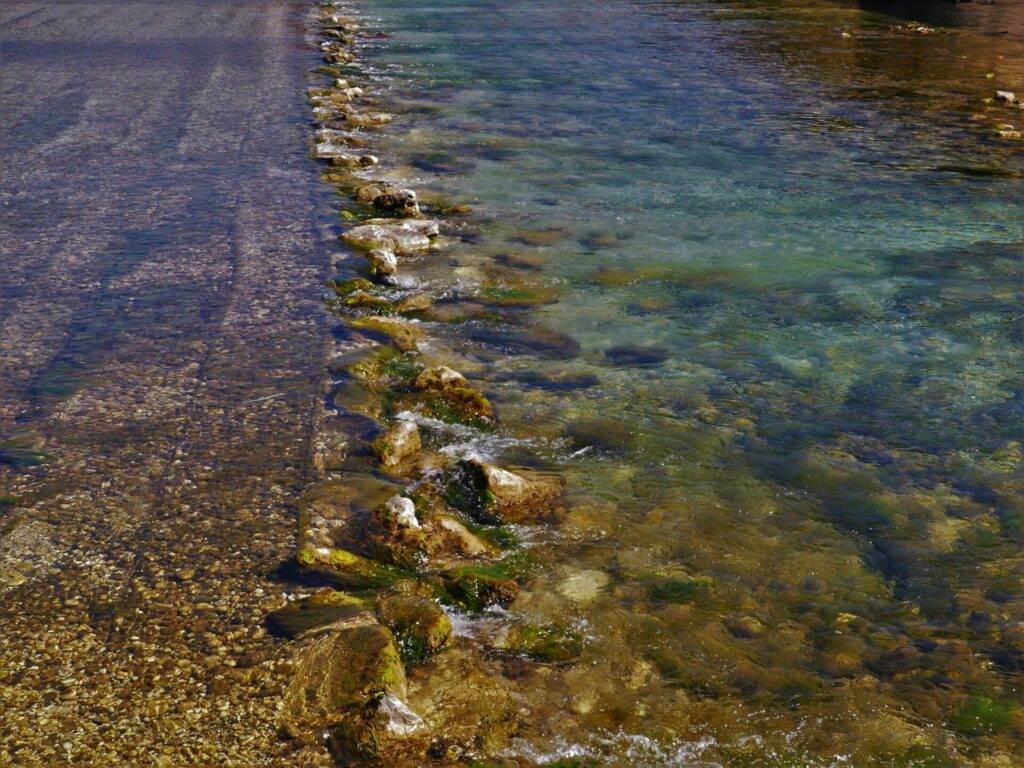

Running like a silver ribbon across the plain, the Arachthos River makes a serpentine turn around Arta town. In earlier times, this quirk of geography was a valuable natural defence, explaining why the founders of the first settlement chose this place sometime between 1900 and 1500 BC.

As long as the town was small and insignificant, there was no reason to build a bridge over its protective river boundary. But in the 3rd century BC, when Arta became the capital of the Kingdom of Epirus, it needed to connect with the hinterland. Archaeologists have discovered that the bridge’s lower visible piers have features similar to the fortifications of Arta’s ancient city, indicating that they may be surviving parts of the original bridge constructed here by King Pyrrhus.

Where the river cuts the earth like a knife, human invention closes the gap.

The span is the fusion of people and their natural landscape, like a symbolic dialogue between civilisation and the wild river. Visiting the bridge, I admire the technique in its classical lines and the expertise with which the craftsmen threw these stone-built arches over the river to connect its banks so long ago.

I’m fascinated by the many folklore tales surrounding the river. Never cross without saying a prayer and washing your hands, because the gods are angered by those who cross without cleansing themselves of evil. When the rain lashes the earth with unrelenting fury, the river dragons wake with their terrible roar and swallow whatever is in their path.

Through locals, I learn that the bridge was built on soft ground, without firm bedrock, which made its foundation extremely difficult. 142 metres long and 3.75 metres wide, its eight small arched gaps were strategically placed between four large asymmetrical arches to help channel the water in case of flooding, easing the pressure on the bridge’s stonework. The total of 12 arches correspond to the 12 Apostles; one that is closed is considered to be Judas.

Arta townspeople explain to me that in 1612, the highest arch was rebuilt with the sponsorship of the grocer Yiannis Thiakoyiannis. His civic-mindedness was funded by a windfall purchase of oil from Algerian pirates; while the barrels he’d bought appeared to contain only oil, they proved to have gold coins hidden at the bottom.

When it was first built, for three years, humans fought with the uncompromising river.

According to legend, 45 craftsmen and 60 apprentices laid the bridge’s foundations under the skilled leadership of the master craftsman. They built all day, but the foundations would collapse each night. The craftsmen mourned, and the apprentices wept: “Woe to our labours, to us, all day long to build and at night for it to be torn down’’. Finally a little bird appeared and spoke to them in a human voice: “If you do not sacrifice someone, the bridge cannot stand. Not an orphan, or a stranger, master craftsman; but your beautiful bride”.

Trying to protect her, the master craftsman sent the bird to his wife with a message: She should take her time, arriving at the building site late in the day. But the bird disobeyed, telling her that her husband needed her immediately: “Hurry, go to the bridge at once!”

When she appeared, the master craftsman’s heart broke. His bride — one of three doomed siblings — then met her fate. As she was being buried alive in the construction, she cried, “Woe to our fate, pity to our destiny! We were three sisters — one was submerged in the Danube, the other buried in the Euphrates, and I, the youngest one, in the bridge of Arta. As the leaf of the tree trembles, let the bridge tremble; and as the leaf falls, let the passers-by fall.” Reminded that her only brother was abroad and might yet pass that way himself, she went on to say, “If the wild mountains tremble, let the bridge tremble, and if the wild birds fall, let the passers-by fall; for I have a brother in a foreign land, lest he should pass.’’

The god of the river needed to be appeased when man interfered in his realm. With the sacrifice of human life, balance was restored and the bridge did not crumble that night.

I become aware of other old customs and stories surrounding the bridge.

When a woman gave birth to a stillborn baby, she would go to the bridge and throw stones into the river. The protector from ancient times — the river with its god granting fertility and abundance — would help her to bear healthy children.

When musicians passed over the span, it was said that the bridge trembled because the she-devil buried within was dancing.

When a bridal procession crossed, the bride dismounted so that the ghost of the sacrificed master craftsman’s bride would not be awakened by the sound of horse’s hooves, envy the young woman’s happiness and make the bridge collapse.

I hear that the famous bridge craftsmen of Epirus set out for all regions of Greece at the feast of St George in spring, returning on the feast of St Demetrius in autumn. Being competitive twins, it’s said that the saints argued over their different roles in people’s lives, as Demetrius accused elder brother George:

I gather the families. You separate them.

I connect mothers with children. You divide them.

I unite spouses. You scatter them.

In their time away, the craftsmen toured the Balkan peninsula building mansions, seraglios, fountains, churches, and mosques. They used their secret language, the Kudaritika, to protect their specialist art. If any one word was learned outside the team, it was quickly replaced by another, new term.

In the vast plains of Arta where the Arachthos flows, the construction material was slate. The connecting mortar was a mixture of ground tiles, lime, pumice stone, soil, water and dry grass. To increase the solidity, egg whites and goat hair were added. The construction started from both sides, slowly progressing to meet towards the top, where the higher arch was completed. The roadbed follows a curved line and is paved with cobblestones.

Gazing at the structure, I am enchanted by the sound of running water and the rustling leaves of a tree moving in the breeze nearby. On the eastern bank of the river by the beginning of the bridge, a large plane tree survives, called the Plane Tree of Ali Pasha. The tree’s legend says that in its shadow sat Ali Pasha, ruler of Epirus during the Turkish Occupation; hanging from its branches were those Greeks he had condemned to death. Commemorating the aftermath of these macabre events, a folk song asks the question: “What is wrong with you, poor plane tree, that you are standing withered with your roots in the water? Ali Pasha has passed on”.

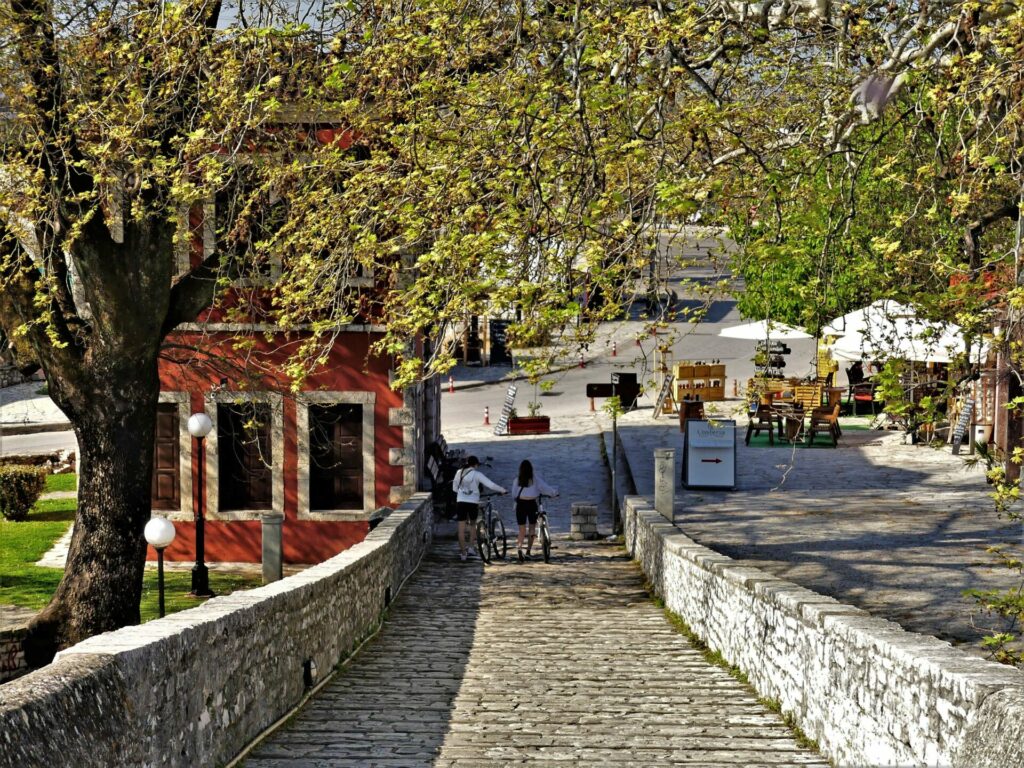

In 1881, Arta was liberated. The bridge itself became the border between Turkish-occupied and free Greece, serving that purpose until the First Balkan War. The bright-red building at the western end, constructed in 1864, today houses the Folklore Museum. It was used as a Bridge Outpost and later as a Customs Office for the Turks.

At the end of 1930, concrete blocks were added to the ancient foundations to support the bridge, which the Germans reinforced with iron beams for their vehicles during World War II. When the Nazis left, they intended to blow up the historic bridge. One soldier, an archaeologist, turned back and deactivated the explosive device. Thus, against the odds the bridge survived the war.

The river flows past me calmly. The bridge reflects on the water, standing patiently, waiting for its passers-by. Endlessly waiting.

Romantic walkers and children on bicycles cross carefully so as not to disturb the unquiet spirit of the master craftsman’s bride; the bridge demystifies the fear of the unknown, the fear of what might lie beyond.

There is always a bridge to get us through life’s difficulties. The road of life, snaking for each of us through obstacles, seeks its bridge to take us to the other side… always finding a way.