Near the church of Nossa Senhora das Necessidades, on an unusually warm winter’s night I peered out over a flotilla of sailboats and across the bay. Behind me, small cars bobbled over the cobblestoned streets of Santo Antônio de Lisboa — an Azorean neighbourhood in the city of Florianópolis — bringing the village to life. As I gazed out over the water, I thought about one of the city’s most famous legends.

When I landed in Brazil in 2012, my Portuguese-language tutor Nathália shared some advice.

She said that many of the Azoreans who settled here during the mid-18th century were really witches escaping persecution in Europe. If I wanted to live a prosperous local life, Nathália said I’d need to recite an incantation before crossing the bridge from the mainland of Santa Catarina state to the island of the same name; home to Florianópolis, the state’s capital.

I had to let the ancient bruxas know that I was coming, and ask for their blessings.

It worked. Otherwise, how else would I have ended up in a place as mystical — and magical — as Santo Antônio de Lisboa?

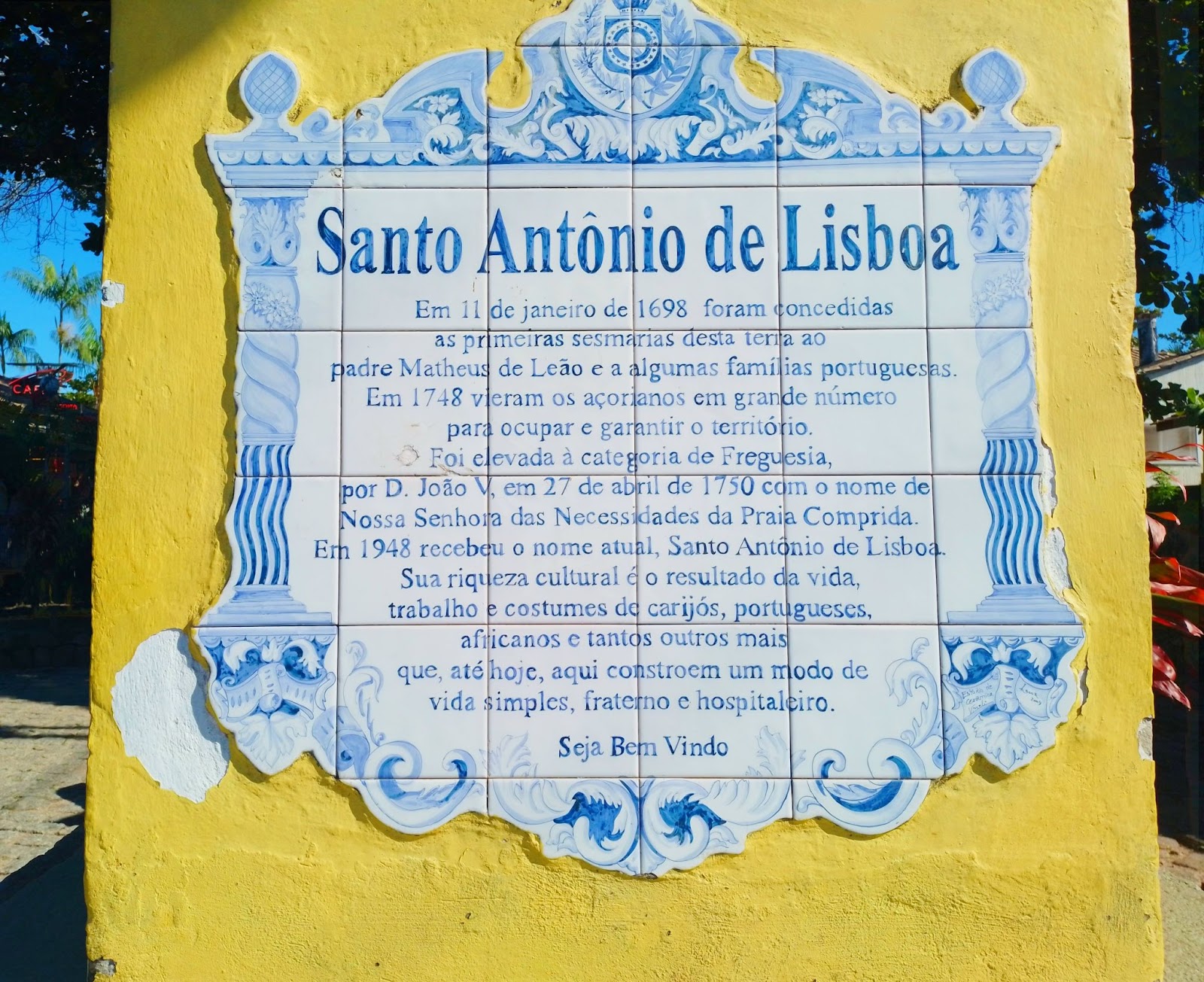

That moment of reminiscing over, my son joined me and we paid a visit to a famous local headstone. We gazed at what was written on the ceramic tiles in front of us. “What does it say?” he asked.

He was born here on this island, Ilha de Santa Catarina as it’s officially called. Much of his early childhood was spent traversing spots like these. But after moving to the southern Caribbean and living there for seven years, the time had come. He needed to reconnect to this place, the one he always called home.

So we packed up our lives and moved back to Florianópolis.

Now, standing at the centre of his new world, fairy lamps above us zig-zagged all the way down to a deck and towards the water’s edge. I pointed to the headstone’s words.

Painted in a deep admiral blue on white azulejos, the inscription greets all visitors who descend the slope and those who venture into the Alfaias artisans’ market during the weekends. Set in concrete, it reduces four hundred years of the seaside village’s history to a polite epitaph that’s about the size of a pub’s TV screen.

I took a deep breath.

“It says that in 1748, the people from the Azores, who sailed across dangerous seas to get here, were finally able to call this place home. And in 1750, Dom João V of Portugal made it a parish. The townsfolk celebrated by paving the main road, so the king could visit. He thanked them by giving the town a really long name. But in 1948, everyone wanted a shorter one. So they changed it to Santo Antônio de Lisboa, whom they all knew as the Holy Matchmaker.“

Of course, some of what I said wasn’t written on the headstone, exactly.

The actual words were too dull for a boy rediscovering the Portuguese language he’d left behind years ago, so I simply threw in some historical facts that really should have made the final cut.

We continued our exploration. “What’s that?” he said, pointing over my shoulder.

It was a restaurant’s sign with an oversized oyster shell for a logo. In fact, eateries just like it dotted the sidewalks all the way to the waterfront. And they all served the one thing that made this place a food sinner’s heaven…

Oysters. Gigantic, succulent oysters. I shot my hands skyward and turned on my heel, beckoning him to follow while exclaiming, “That’s why this place exists!”

During the mid-1980s, Santo Antônio de Lisboa was a town in a downward spiral. It had long lost its prominence as the island’s main port. The waters were overfished. Businesses were shuttering. And the opportunities for locals were anywhere but here.

That’s when a group of researchers from the Federal University of Santa Catarina’s Marine Mollusks Laboratory (MML) dared to change the town’s fortunes. In the coves that marked the narrow stretch of water between the island and the mainland, they felt it possible to spark an industry from scratch.

With its waters ripe for growing microalgae to feed oysters, Santo Antônio de Lisboa was the perfect test environment candidate.

First, they tried cultivating the native oyster species, typically grown in mangroves. It didn’t work.

Then the researchers made another foray, this time transplanting Japanese oysters grown in the Pacific Ocean. The result was better, but not yet perfect; with warmer summer temperatures in Florianópolis, the mortality rates for the oyster spats were still too high to make the operation viable.

So the MML team took the long way around to solving the problem; they reproduced the surviving oysters in the lab, thus accelerating the process of natural selection.

This time, they succeeded… and the oyster industry took off.

Almost four decades later, the MML has a station in Barra da Lagoa which produces about 45 million seedlings for oyster farmers across the island.

On average, it takes oyster breeders in France close to three years to complete a growth cycle. But with a highly optimised system, mariculturists in Florianópolis can go from larvae to lunch-ready in only seven months.

Families have since returned to Santo Antônio de Lisboa. They’ve set up organic oyster farms that feed not only the local restaurants but roughly 95% of Brazil’s oyster, mussel and scallop consumption.

With the ability to filter up to 20 litres of seawater per day, and hold 12 grams of carbon for every 100 grams of shell, oyster culture in Santo Antônio de Lisboa is teaching new legions of local producers profitable lessons in preserving their waters.

Over the last decade, once-rare species of fish and crustaceans have returned to the bay. But this time, respect for the ecosystem runs deep. The state’s agricultural watchdog, CIDASC, tests the water quality every two weeks. If anything is amiss, they shut down the entire industry until the problem is fixed.

As we wound our way through artisan stalls and couples holding hands, we passed craft galleries, ice-cream cafés and chalkboard menus a bit too big for the sidewalks.

I glanced at my son. His eyes glimmered with awe as he took in the Azorean architecture. I nudged him with an elbow asking, “Are you happy here?“ He looked up, smiled and said, “I am”.

Once more, the witches had listened. And once more, they blessed me.